The day Mumbai shook like Hiroshima; 1300 dead, city showerd with gold (Vaikom Madhu)

Published on 26 April, 2014

(The writer lived in Mumbai as a budding journalist to dig up shreds of a horrible past)

Gold is being dug up not just by Air Customs officials, but from beneath the muddy waters of Mumbai Sea at irregular intervals.

Ferdinand Roberts realises for the first time that his father went up in smoke in a heroic rescue operation, now submerged in the mire of history. Miracles do happen. The disappearance of Malaysian Airlines’ flight MH 370 in mid-air is not the only one to qualify thus.

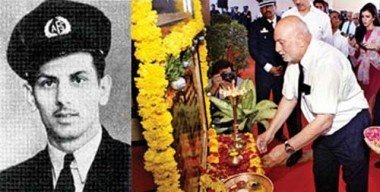

Now turns the spotlight on Ferdinand Oswald Eugene Roberts, aka, Ferdinand Roberts. Indian, but British; Anglo yet Aussie. The 70-year old man travels to India from Australia the other day to have a look at his never-before-seen father’s name etched on a plaque erected at Byculla, Mumbai, on Fire Service Day and sob inconsolably.

Ferdinand Roberts had heard many stories from his mother but very little about how his father died. He was in Fire Service and died in accident during IInd World war is all that he had heard from his mother on his repeated queries. Growing up as a child without a father he was always curious to know how he had died prematurely.

His mother was six month pregnant with him when his father Sr Ferdinand Roberts died. His widowed mother, 22 years old then, married his father’s older brother and left Mumbai to live in England. “When I used to ask my mother how my father died, all she would tell me was that he was in the fire brigade and that he died in the war,” Roberts reminisces. It was on Monday, April 14 2014, that Roberts finally knew the details of his father’s death.

Roberts, having moved to Australia at age 26 in 1968 to pursue a career in cinema advertising, now lives there with his second wife. His father was one of ten children, of which four are still alive. His father’s older brother, his stepfather, died in 1974; his mother in 1988.

Roberts will turn 70 this September, as the anniversary of an earth shaking event is commemorated in its 70th year. The details of the event are scarcely known even to Mumbaites, except to some of the Sr. Citizens who have seen gold bars raining down and smoke engulfing downtown Mumbai.

Roberts had never seen his father, for he was born five months after the fateful day in Bombay. Says Roberts: “I was born on Sep 3, 1944, six months after my father died. Today as I stood at the memorial, I felt proud that my father and fallen firemen were remembered in this way for their service,” he said in Mumbai.

One day, while surfing the Internet, he chanced upon a video on YouTube that suddenly told him the truth about his father’s death.

As a fireman aboard the freighter SS Fort Stikine, his father had perished along with hundreds of people in the explosion that tore the vessel apart just off the Mumbai docks on April 14, 1944. Learning that the Fire Safety Week is observed in the state of Maharashtra between April 14 and 21 in honour of the 66 firemen that died that day through the video, he asked to be invited to the event. Visiting Mumbai close to 60 years after leaving as a boy to live in London, Ferdinand Oswald Eugene Roberts stood at the memorial bearing his father’s name, the same as his own, with tears in his eyes.

Roberts, an Anglo-Indian, has not been to India ever before. He and his my family had left for England in 1951.

The worst man-made disaster, second only to Bengal famine, evokes memories of nearly 1300 persons chocked/burned to death and huge collateral damages caused to buildings and ships this month and year, 70 years ago.

Gold bars flew across the city. Crates of ammunition banged spewing fire and smoke that engulfed the entire Port area sending hundreds of people to death, coughing and suffocating. A number of birthed ships sank.

A tragedy of that magnitude was unheard of by the citizens of Bombay (now Mumbai), nor can be traced in the recorded history of the sprawling City, then part of British Raj.

This writer reached Bombay 15 years later searching for a job.I learned of the catastrophe from the casual talks between elder migrants of the city while commuting suburban trains.

My later on acquaintances had also heard from word of mouth sketchy descriptions of the chilling disaster. But I can recall some of the victims I had met with, in different parts of the city mostly on occasions quite accidental or in the company of my local Marathi friends.

Victims who bore marks of the Bombay Dock Blast, as was it known then, victims who were incapacitated for life, left blind, deaf, maimed, amputated or unattended.

The ship had also in its hold £890,000 worth of gold bullion in bars in 31 crates. The Freighter caught fire and was destroyed in two giant blasts, scattering debris, sinking surrounding ships and setting fire to all that were in and around the Port zone killing around 800 people.

The ship had arrived at the docks from Karachi on 12th April, two days earlier.

In the mid-afternoon around 14:00, the crew were alerted to a fire onboard burning somewhere in the No. 2 hold. The crew, dockside fire teams and fireboats were unable to put out the fire, despite pumping over 900 tons of water into the ship, nor were they able to find the source due to the dense smoke. The water was boiling all over the ship, due to heat generated by the fire. A piece of propeller landed in St. Xaviers High School, about 4.8 km from the docks.

The details of the explosions and losses were first reported to the outside world in detail by Radio Saigon, a Japanese-controlled radio on 15 April 1944. British-Indian wartime censorship permitted news reporters to send the reports only in the second week of May 1944. TIME Magazine published the story as late as 22 May 1944 and still it was news to the outside world. A movie depicting the explosions and aftermath, made by Indian cinematographer Sudhish Ghatak, was confiscated by military officers although parts of it were shown to the public as a newsreel at a later date.

Journalist Shashikala Baliga’s uncle, who was a deaf, heard the blast, making it the only sound he ever heard in his life.

What kind of Captain would accept such a cargo. Every manuel, every handbook, warns against carrying cotton and explosives together. But Capt Naismith had little choice. England expected every man to do a duty and Captain’s duty was to carry full load in war time. It was war time and the ship did not carry a red flag indicating explosives.

Flying a red flag may make a natural target for Japanese, against whom allies were fighting a war then.

The fire in the Port died out a long while ago, but the ember keeps showing up shrugging off its ash in the memory of living descendents of legions of Roberts.

Gold is being dug up not just by Air Customs officials, but from beneath the muddy waters of Mumbai Sea at irregular intervals.

Ferdinand Roberts realises for the first time that his father went up in smoke in a heroic rescue operation, now submerged in the mire of history. Miracles do happen. The disappearance of Malaysian Airlines’ flight MH 370 in mid-air is not the only one to qualify thus.

Now turns the spotlight on Ferdinand Oswald Eugene Roberts, aka, Ferdinand Roberts. Indian, but British; Anglo yet Aussie. The 70-year old man travels to India from Australia the other day to have a look at his never-before-seen father’s name etched on a plaque erected at Byculla, Mumbai, on Fire Service Day and sob inconsolably.

Ferdinand Roberts had heard many stories from his mother but very little about how his father died. He was in Fire Service and died in accident during IInd World war is all that he had heard from his mother on his repeated queries. Growing up as a child without a father he was always curious to know how he had died prematurely.

His mother was six month pregnant with him when his father Sr Ferdinand Roberts died. His widowed mother, 22 years old then, married his father’s older brother and left Mumbai to live in England. “When I used to ask my mother how my father died, all she would tell me was that he was in the fire brigade and that he died in the war,” Roberts reminisces. It was on Monday, April 14 2014, that Roberts finally knew the details of his father’s death.

Roberts, having moved to Australia at age 26 in 1968 to pursue a career in cinema advertising, now lives there with his second wife. His father was one of ten children, of which four are still alive. His father’s older brother, his stepfather, died in 1974; his mother in 1988.

Roberts will turn 70 this September, as the anniversary of an earth shaking event is commemorated in its 70th year. The details of the event are scarcely known even to Mumbaites, except to some of the Sr. Citizens who have seen gold bars raining down and smoke engulfing downtown Mumbai.

Roberts had never seen his father, for he was born five months after the fateful day in Bombay. Says Roberts: “I was born on Sep 3, 1944, six months after my father died. Today as I stood at the memorial, I felt proud that my father and fallen firemen were remembered in this way for their service,” he said in Mumbai.

One day, while surfing the Internet, he chanced upon a video on YouTube that suddenly told him the truth about his father’s death.

As a fireman aboard the freighter SS Fort Stikine, his father had perished along with hundreds of people in the explosion that tore the vessel apart just off the Mumbai docks on April 14, 1944. Learning that the Fire Safety Week is observed in the state of Maharashtra between April 14 and 21 in honour of the 66 firemen that died that day through the video, he asked to be invited to the event. Visiting Mumbai close to 60 years after leaving as a boy to live in London, Ferdinand Oswald Eugene Roberts stood at the memorial bearing his father’s name, the same as his own, with tears in his eyes.

Roberts, an Anglo-Indian, has not been to India ever before. He and his my family had left for England in 1951.

The worst man-made disaster, second only to Bengal famine, evokes memories of nearly 1300 persons chocked/burned to death and huge collateral damages caused to buildings and ships this month and year, 70 years ago.

Gold bars flew across the city. Crates of ammunition banged spewing fire and smoke that engulfed the entire Port area sending hundreds of people to death, coughing and suffocating. A number of birthed ships sank.

A tragedy of that magnitude was unheard of by the citizens of Bombay (now Mumbai), nor can be traced in the recorded history of the sprawling City, then part of British Raj.

This writer reached Bombay 15 years later searching for a job.I learned of the catastrophe from the casual talks between elder migrants of the city while commuting suburban trains.

My later on acquaintances had also heard from word of mouth sketchy descriptions of the chilling disaster. But I can recall some of the victims I had met with, in different parts of the city mostly on occasions quite accidental or in the company of my local Marathi friends.

Victims who bore marks of the Bombay Dock Blast, as was it known then, victims who were incapacitated for life, left blind, deaf, maimed, amputated or unattended.

The ship had also in its hold £890,000 worth of gold bullion in bars in 31 crates. The Freighter caught fire and was destroyed in two giant blasts, scattering debris, sinking surrounding ships and setting fire to all that were in and around the Port zone killing around 800 people.

The ship had arrived at the docks from Karachi on 12th April, two days earlier.

In the mid-afternoon around 14:00, the crew were alerted to a fire onboard burning somewhere in the No. 2 hold. The crew, dockside fire teams and fireboats were unable to put out the fire, despite pumping over 900 tons of water into the ship, nor were they able to find the source due to the dense smoke. The water was boiling all over the ship, due to heat generated by the fire. A piece of propeller landed in St. Xaviers High School, about 4.8 km from the docks.

The details of the explosions and losses were first reported to the outside world in detail by Radio Saigon, a Japanese-controlled radio on 15 April 1944. British-Indian wartime censorship permitted news reporters to send the reports only in the second week of May 1944. TIME Magazine published the story as late as 22 May 1944 and still it was news to the outside world. A movie depicting the explosions and aftermath, made by Indian cinematographer Sudhish Ghatak, was confiscated by military officers although parts of it were shown to the public as a newsreel at a later date.

Journalist Shashikala Baliga’s uncle, who was a deaf, heard the blast, making it the only sound he ever heard in his life.

What kind of Captain would accept such a cargo. Every manuel, every handbook, warns against carrying cotton and explosives together. But Capt Naismith had little choice. England expected every man to do a duty and Captain’s duty was to carry full load in war time. It was war time and the ship did not carry a red flag indicating explosives.

Flying a red flag may make a natural target for Japanese, against whom allies were fighting a war then.

The fire in the Port died out a long while ago, but the ember keeps showing up shrugging off its ash in the memory of living descendents of legions of Roberts.

Facebook Comments

Leave A Reply

മലയാളത്തില് ടൈപ്പ് ചെയ്യാന് ഇവിടെ ക്ലിക്ക് ചെയ്യുക

അസഭ്യവും നിയമവിരുദ്ധവും അപകീര്ത്തികരവുമായ പരാമര്ശങ്ങള് പാടില്ല. വ്യക്തിപരമായ അധിക്ഷേപങ്ങളും

ഉണ്ടാവരുത്. അവ സൈബര് നിയമപ്രകാരം കുറ്റകരമാണ്. അഭിപ്രായങ്ങള് എഴുതുന്നയാളുടേത് മാത്രമാണ്. ഇ-മലയാളിയുടേതല്ല